04 Coriolis Merry-go-Round#

Aim#

To have students experience forces (centrifugal and Coriolis) in a rotating frame of reference.

Subjects#

1E20 (Rotating Reference Frames)

1E30 (Coriolis Effect)

Diagram#

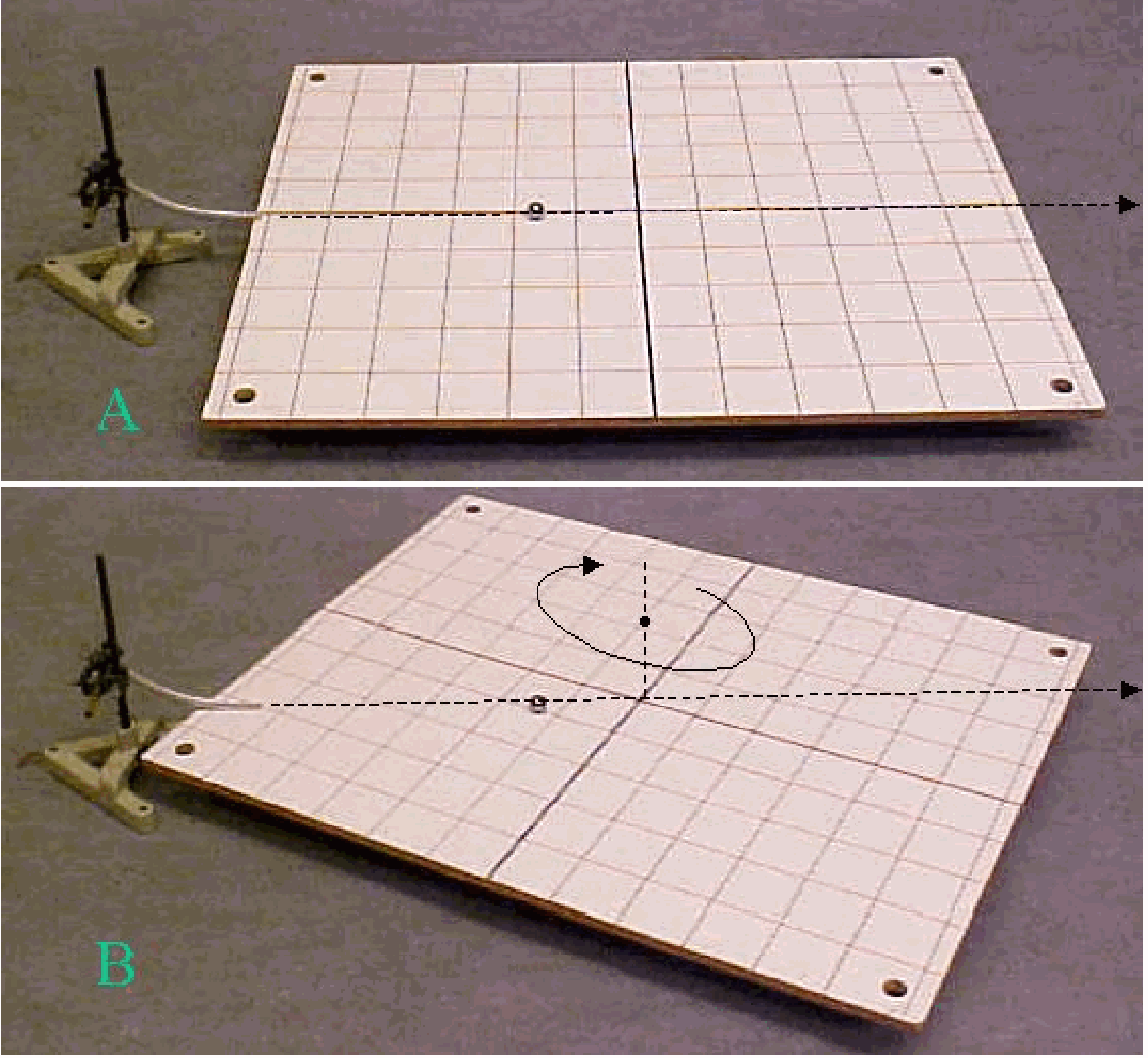

Fig. 54 .#

Equipment#

Merry-go-round; \(r=3\mathrm{~m}\); closed to the outside world.

Basketball.

Plumb line.

High-speed gyroscope.

Rifle (fixed firmly on a support) and target.

Water-basin (with a central drain) that can easily be leveled horizontally (for standing still and in case of rotation).

Instructor and students (maximum 12).

Safety#

The merry-go-round rolls on rubber wheels over a circular rail. A circular sheet of stiff rubber prevents contact with the wheels (see the black rubber sheet in the pictures in the Diagram).

On both sides of the merry-go-round, there is an emergency-stop button. Pressing any one of these buttons will stop the merry-go-round immediately. There is also an emergency-stop button on the inside.

When a group is practising inside, an observer must remain outside the merry-go-round to ensure safety.

Presentation#

We have merry-go-round sessions with 12 students at a time. In such a session, experiencing the Coriolis force by the students is the main objective. To limit the experience to the rotating reference frame, there are no windows, and both doors are closed. (No sight to the outside world also limits the chance of becoming sick.) The students enter and position themselves along the wall (not leaning against, but free from the wall).

Standing still.

When the group is inside, we first observe some phenomena while the merry-go-round is remains still: – Watch the plumb line standing near the wall of the platform, with its plumb bob directed towards the centre of the disc beneath it.

Observe the rotating gyroscope, whose axis of rotation remains firmly fixed in one direction.

Fire a lead shot at the target across the diameter of the merry-go-round and note the position of the hole it creates.

Small pieces of paper are scattered on the water surface in the basin. When the plug is pulled from the drain, students observe how the water flows in straight lines towards the drain; the pieces of paper reveal the streamlines converging towards the depression.

Rotating.

The group stands along the outside wall of the platform. The platform is rotated at full speed. For a short while, one door is left open so the students can see that we are rotating, but then it is closed, placing us firmly in our rotating frame of reference. At full speed, the platform takes about 5 seconds to complete one full rotation. This speed is not too fast and remains comfortable. (Outside the merry-go-round, it moves at roughly walking speed: while walking, you can keep pace with the merry-go-round.)

Having no sight of the outside world, we soon forget that we are rotating, but:

Watch the gyroscope! Its frame is rotating! Since we know that a gyroscope has its axis of rotation fixed in space when no external torques are applied. The rotating frame of the gyroscope indicates that we are rotating in the opposite direction.

Watching the students, you see them leaning towards the centre a little. Make them notice this and show them what the plumb line is doing. Also, this plumb line is “leaning”; the plumb is forced outward: the centrifugal force.

The Coriolis force comes into play whenever there is movement. Now, the students are asked to move around — this is the fun, laughter part of the session: “drunken” people walking around. Then, ask them to observe the direction in which they experience a force on their moving body. Soon, everyone will conclude that when moving forward, there is a force to the left (our merry-go-round rotates clockwise when viewed from above). Also, note that this force is felt everywhere on the platform and that it does not depend on the direction you walk. Knowing that \(F_{\text {Coriolis }}=-2 m \vec{\omega} \times \vec{v}\), they can check the direction of the force vector they are experiencing. The negative sign in the formula is relevant! They can also check that the Coriolis force is higher when \(\bar{v}\) is higher by trying a speed walk.

Now that they “know” through experience what the Coriolis force is all about, the students sit down along the outside wall. A basketball is handed to one of them, and this person is asked to name somebody facing him. When there is visual contact, the ball is rolled towards the opposing person. This is the second laughter part of the session, because despite their Coriolis experiences they just had, they usually don’t expect the (left-going) curves the ball will make. It takes some time before every try is successful. When they succeed, they can also try throwing the ball instead of rolling.

We tell the next story: “When the forward rolling ball is continuously deflected to the side, wouldn’t it be possible to roll the ball at such a speed that it will return to the one that made it rolling, the ball just going round in a circle?” We make them think about it for a short while, and when they think they have an answer, we let them try. Usually, it takes several endeavors before a successful circle is followed by the ball that rolls along the wall. Following this, we ask what a spectator outside the merry-go-round would see when he looks at the ball (supposing the walls are made of glass). It usually takes some discussion before they realize that the outside spectator sees the ball standing still.

We pose the question: “Into which direction do you have to walk so that the centrifugal force and Coriolis force are opposing each other, and when you think you know the answer, try it.” After some time, everybody walks in the right direction: along the wall, opposite to the rotation of the merry-go-round. Make them notice that they walk easily! They feel no force at all! So, probably the centrifugal and Coriolis forces cancel each other. (Centrifugal force is directed away from the centre of the merry-go-round, while Coriolis force is directed towards the centre of the merry-go-round.) Invite them to predict what they will feel when they walk in the other direction: Both forces are pointing outwards, and that can be felt strongly when doing so! Make them walk again in the opposing-forces direction and ask them what somebody outside the merry-go-round would see if the walls of the merry-go-round were made of glass. That somebody would see them standing still! While walking, the floor is moving under their feet! After this experience, we will shortly discuss the concept of fictitious force: Somebody outside the merry-go-round sees you standing still, and they will conclude that there is no force acting on you. But you, inside the merry-go-round, need to talk about centrifugal force and Coriolis force, which oppose each other.

Before we fire a shot, we ask the students to predict where the shot will hit the target now, knowing that the bullet has a high speed ( \(150 \mathrm{~m} / \mathrm{s}\); the bullet travels in around \(0.03 \mathrm{~s}\) across the diameter of the merry-go-round). They usually predict: to the left of the hole made when standing still, but just a little, because the bullet has such a high speed. The shot is fired, and to their surprise, it is a relatively large displacement! Knowing \(F_{\text {Coriolis }}=-2 m \vec{\omega} \times \bar{v}\), they can realize that due to the high \(\vec{v}\), also \(F_{\text {Coriolis }}\) is high now.

The water basin is levelled in this rotating situation such that the water is level with the basin. This is done by removing the two wooden blocks under the two inner legs. When the water is stable, we ask the students what will happen to the streamlines when we pull the plug. Rotation is predicted, but very often in the wrong direction. Discussing the direction of the Coriolis force will make their prediction right. We pull the plug and see that the water starts streaming in straight lines, but very soon they are bending to the left and move towards the drain in a clockwise rotation. The water leaves the drain very slowly now.

Remarks#

Do not lean against the wall. The wall is made of very light material and will not withstand a large force.

We have two opposing doors in our merry-go-round. Since the merry-go-round moves very close to one wall, the second door is sometimes needed when we stop the merry-go-round and want to leave it.

Sources#

Giancoli, D.G., Physics for scientists and engineers with modern physics, pag. 292-294

McComb,W.D., Dynamics and Relativity, pag. 137-140 and 145