02 Irreversible process#

Aim#

To show that the likelihood of the occurrence of a reverse process can be so small as to be completely negligible.

Subjects#

4F10 (Entropy)

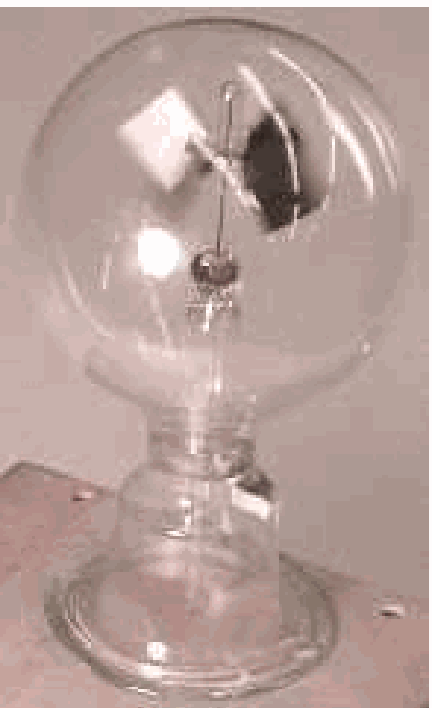

Diagram#

Fig. 422 .#

Equipment#

Glass basin; \(\varnothing = 15 \mathrm{~cm}\)

Drop of ink.

Overhead projector.

(tennis) Ball.

Presentation#

The glass basin is filled with a layer of water. This is projected (DiagramA). Then a drop of ink is carefully placed on the surface of the water. The drop slowly spreads itself in the water (DiagramB).

During the explanation (see Explanation) the continuing spreading of the drop can be observed by the students and at the end of the lecture they see the almost homogeneous distribution of the ink drop in the water (DiagramC).

Seeing the continuing spreading of the ink drop, we can also say that the homogeneous distribution of the ink drop is the most probable state of the fluid in the glass basin.

Explanation#

The irreversibility of this mixing process is well known to the students; it corresponds to their own experiences. New is the concept of probability linked to this process. To illustrate this a tennis ball is given to one student in the middle of a complete row of students sitting in the lecture hall and they are asked to pass this ball in that row, unseen to other students, arbitrary from left to right. After some time you ask the other students to tell where the ball is: is it on the left side of the lecture hall or on the right side? After short discussion their answer will be that the probability for either side is \(50 \%\). Then the same question is posed in case we suppose that two balls are in the row: What is the chance that both balls are on one side? \(25 \%\), that will be their answer. The general rule is that the chance of finding all balls on one side is \((.5)^{n}, \mathrm{n}\) being the number of balls involved. So with 4 balls that chance is \((.5)^{4}=1 / 16\). The table shows the 16 possible states. With 10 balls the chance is 0.00098 (around \(.1 \%\) ) and with 100 balls: \(7.9 \times 10^{-31}\), showing that the chance decreases very rapidly with the number \(\mathrm{n}\).

A drop of ink (a sphere of “water” with a diameter of \(1 \mathrm{~mm}\) ) contains around \(2.5 \times 10^{15}\) molecules. So the chance to find all these molecules on one side of the basin equals \((.5)^{2.5 \times 10 E 15}\). This is such an extremely small number, that it will never happen during any physically meaningful period of time.

Finding the ink drop just as “a drop” has a chance that is even lower.

So that will never happen.

Possible states of 4 balls \(A, B, C\) and D |

Total |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

4 left |

\(ABCD/-\) |

1 |

|||||

3 left; 1 right |

\(ABC/D\) |

\(A B D / C\) |

\(A C D / B\) |

\(BCD / A\) |

4 |

||

2 left; 2 right |

\(A B/C D\) |

\(AC/BD\) |

\(AD / BC\) |

\(BC/AD\) |

\(BD/AC\) |

CD/AB |

6 |

1 left; 3 right |

\(A/BCD\) |

\(B/ACD\) |

\(C/ABD\) |

\(D/ABC\) |

4 |

||

4 right |

\(-/ABCD\) |

1 |

In the table above we see that the situation with 2 balls left and 2 balls right is the most probable state. This is also the most homogeneous distribution of the 4 balls. And this corresponds to the homogeneous distribution of the fluids in the glass basin; so this is the most probable state.

Sources#

PSSC, College Physics, pag. 394-396

Giancoli, D.G., Physics for scientists and engineers with modern physics, pag. 535-537