03 Mortar#

Aim#

To show an example in which the principle of conservation of mechanical energy is very helpful.

Subjects#

1M40 (Conservation of Energy)

Diagram#

Fig. 147 .#

Equipment#

Compression spring (we use \(k=2500\mathrm{~N/m}\)).

Launching tube (\(\varnothing=19\mathrm{~mm}\)), soldered into heavy base.

Steel ball, (\(\varnothing=18\mathrm{~mm}\)).

Steel pin.

Measuring tape.

Helmet (see Safety).

Safety#

The steel ball leaves the launching tube with high speed: do not cast a glance into the launching tube and be away with your head when launching.

What goes up will come down. Wear your helmet when you make high launches.

Presentation#

The dimensions of the components are such that when the mortar is assembled, the top of the steel ball is just level with the top of the launching tube (see Figure 148).

Fig. 148 .#

The launching tube has holes drilled in it at every \(\mathrm{cm}\), starting from the top. The steel pin is placed at \(1 \mathrm{~cm}\) from the top; the ball and spring are placed into the launching tube from the bottom side. The base is hold by hand and firmly holds the launching tube down (see Diagram). In this situation the spring is compressed \(1 \mathrm{~cm}\). By means of your other hand the steel pin is pulled out and the steel ball is launched: it just climbs a couple of centimeters. By repeating the demonstration, a numerical value of the elevation can be given.

The whole procedure is repeated but now the steel pin is placed \(2 \mathrm{~cm}\) from the top (and so the spring is compressed \(2 \mathrm{~cm}\) ). Before launching it, make your students predict the maximum height of the steel ball. After their prediction put on your helmet. The ball is launched and the maximum height determined; the prediction is checked (it will be around four times higher).

To complete the demonstration the spring is compressed \(4 \mathrm{~cm}\) (this needs quite some force). Make students predict that the ball easily reaches the top of the lecture hall. The ball is launched, climbs really high, but does not reach the ceiling as predicted. Repeat the experiment and make the students observe that also the compression spring is launched out of the tube: so part of the potential spring energy is transferred into translational kinetic energy of the spring.

Explanation#

When the spring is compressed it will have a potential energy of \(U_{p}=1 / 2 \mathrm{k} \delta^{2}\). ( \(\delta\) is the compression of the spring.) When all this potential energy is transferred to the steel ball, the velocity of the steel ball, when leaving the launching tube, can be determined by \(1 / 2 m_{b(a l l)} v_{i}^{2}=1 / 2 k \delta^{2}\). The maximum height reached \(\left(h_{m}\right)\) can be determined by \(1 / 2 m_{b} v_{i}^{2}=m_{b} g h_{m}\). So, \(h_{m}=\frac{k \delta^{2}}{2 m_{b} g}\), showing the fourfold in \(h_{m}\) when \(\delta\) is doubled.

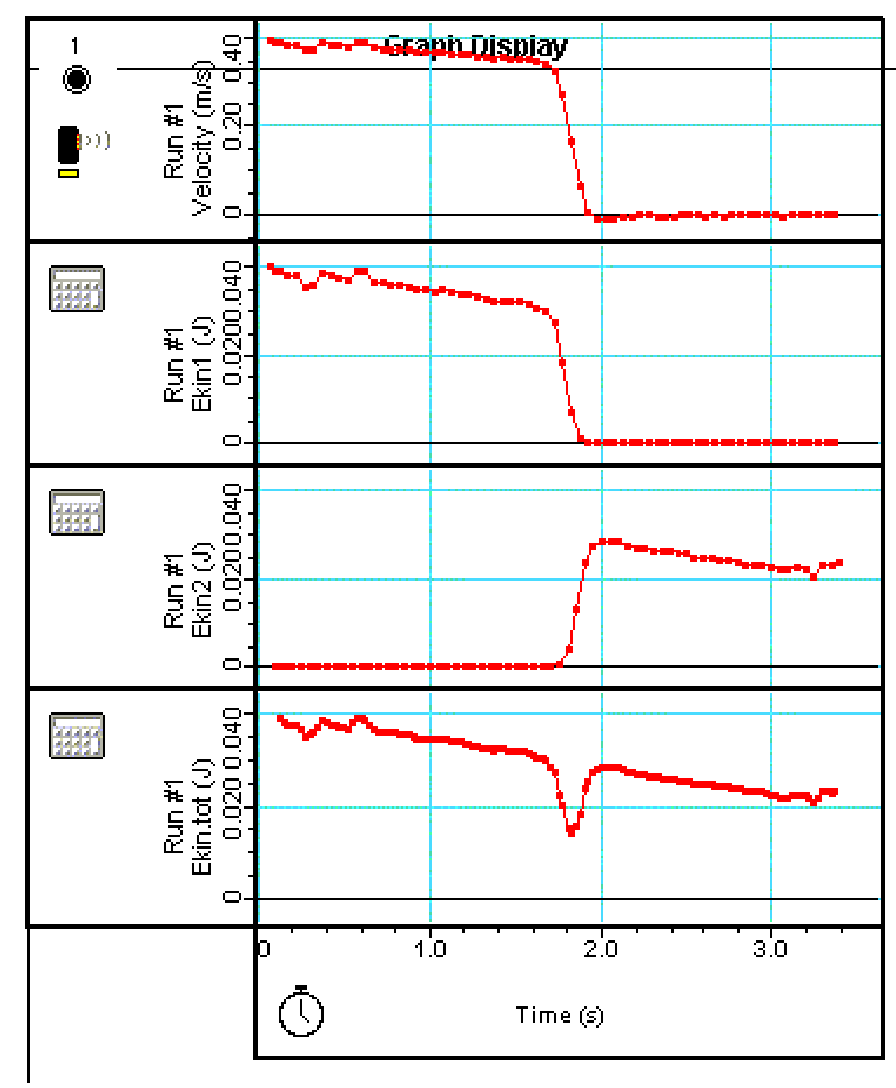

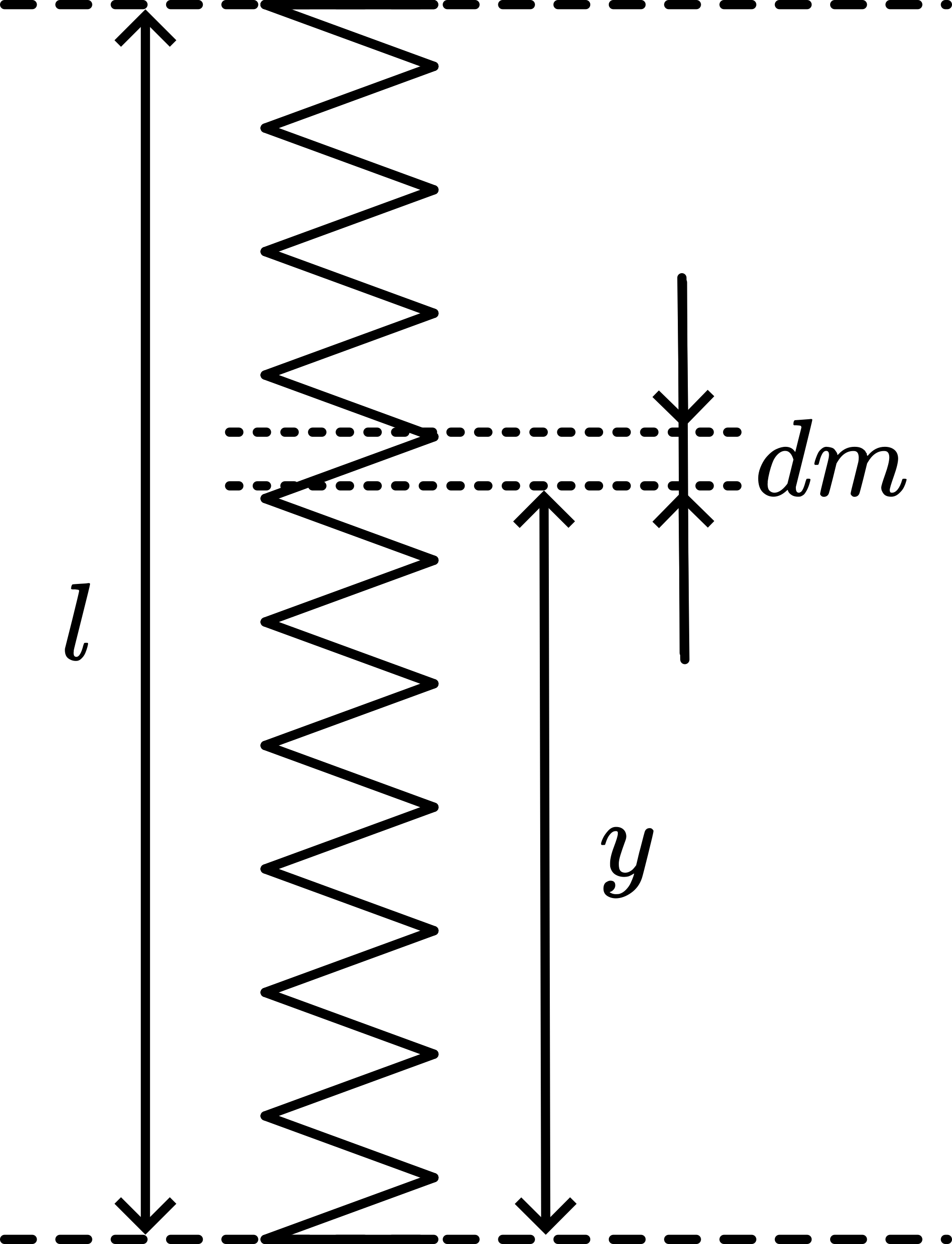

But also the spring is launched! At the moment of launching the top of the spring has a speed \(v_{i}\) (same speed as the steel ball). At that moment the bottom of the spring is still at rest. Every part of the spring has a different speed during the launching process, so in order to determine the kinetic energy of the spring we consider a part ( \(\mathrm{dm}\) ) of it (see Figure 149):

At the moment of launching

\(v_{l}=v_{i}\) and \(v_{y}=y / l . v_{i}\)

Then:

Fig. 149 .#

In our demonstration spring and steel ball have equal mass, so we have that \(1 / 4\) of the potential spring energy is transferred into translational kinetic energy of the spring and \(3 / 4\) is left as kinetic energy for the steel ball. The energy-balance equals \(m_{b} g h_{m}+\frac{1}{6} m_{s} v_{i}^{2}=\frac{1}{2} k \delta^{2}\) and it is clear that doubling \(\delta\) no longer doubles \(h_{m}\).

Remarks#

Using the value of the spring constant given in Equipment, hm can also be calculated in advance and checked in the demonstration.

When we simulate this demonstration in a program like Interactive Physics we observe that the spring not only obtains translational kinetic energy but also vibrational kinetic energy. So the analysis is still a bit more complicated than given in our Explanation. (Adding this simulation to your demonstration shows the value of such a simulation program, since it extends your analysis of the demonstration.)

Sources#

Mansfield, M and O’Sullivan, C., Understanding physics, pag. 60-62 and 87-92.

McComb,W.D., Dynamics and Relativity, pag. 32-35.

Roest, R., Inleiding Mechanica, pag. 49-51; 72-73 and 81-83.