08 Spinning Bouncing Ball#

Aim#

To show the power of the correspondence between translational and rotational motion.

Subjects#

1N20 (Conservation of Linear Momentum)

1Q40 (Conservation of Angular Momentum)

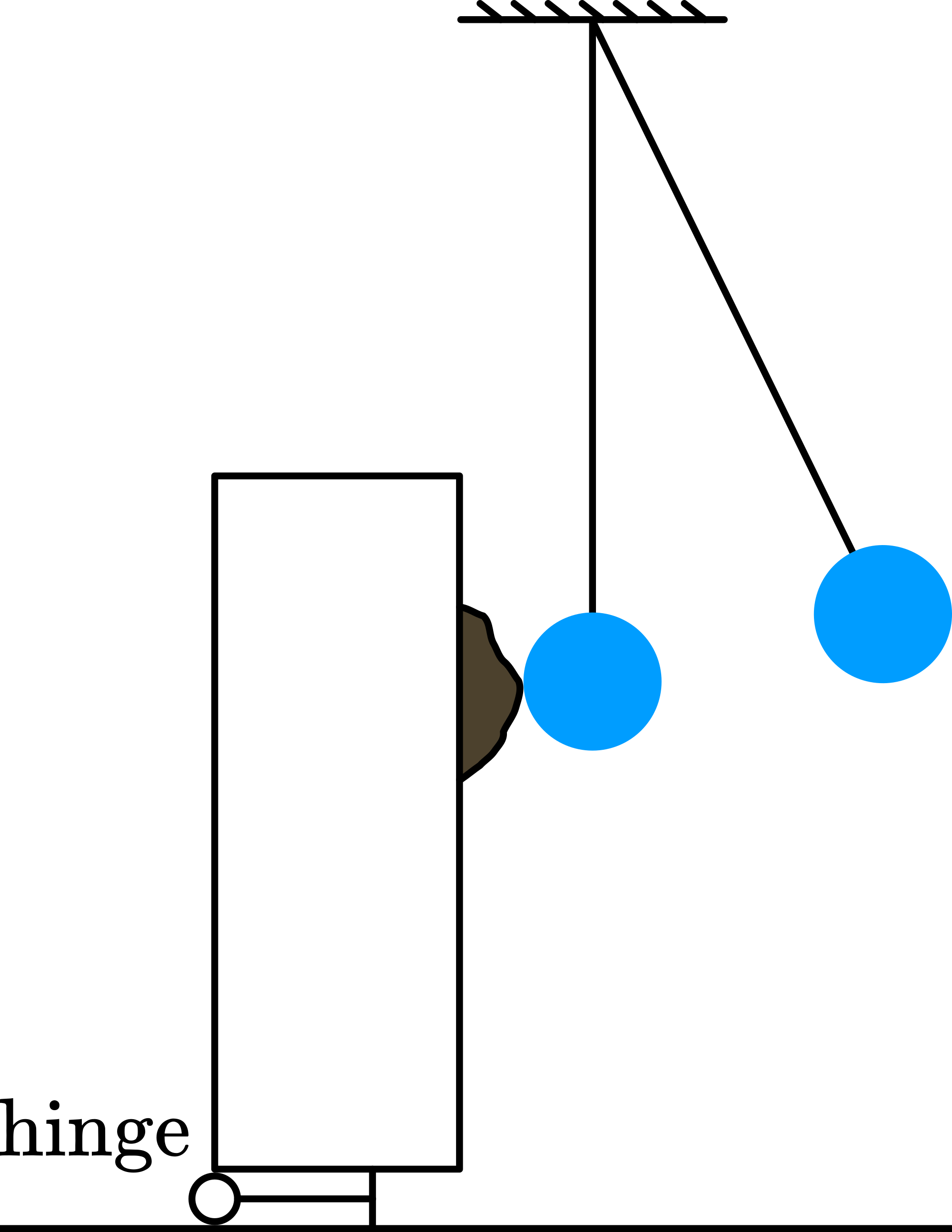

Diagram#

Fig. 177 .#

Equipment#

Racquetball.

Racquetball with straws (Diagram C).

Superball (see Explanation).

Basketball (see Explanation).

Camera

Projector, to project the image of the bouncing ball to a large audience.

Presentation#

The racquetball is dropped straight down from your hand and bounces back (see drawing A in Diagram). This is a well known phenomenon. The laws of mechanics explain the reversal of the velocity (see Figure 178).

Fig. 178 .#

There is a strong correspondence between the formalisms of translational and rotational mechanics. Awareness of this correspondence leads us to the prediction that when the bouncing ball is spinning in one direction when dropped, it has to spin in the opposite direction after bouncing! (see drawing B in Diagram.)

We try this and it really works that way! (The camera looks down on the bouncing ball and “sees” the label on the ball rotate in one direction and after bouncing in the other direction, and so on, while bouncing.)

Explanation#

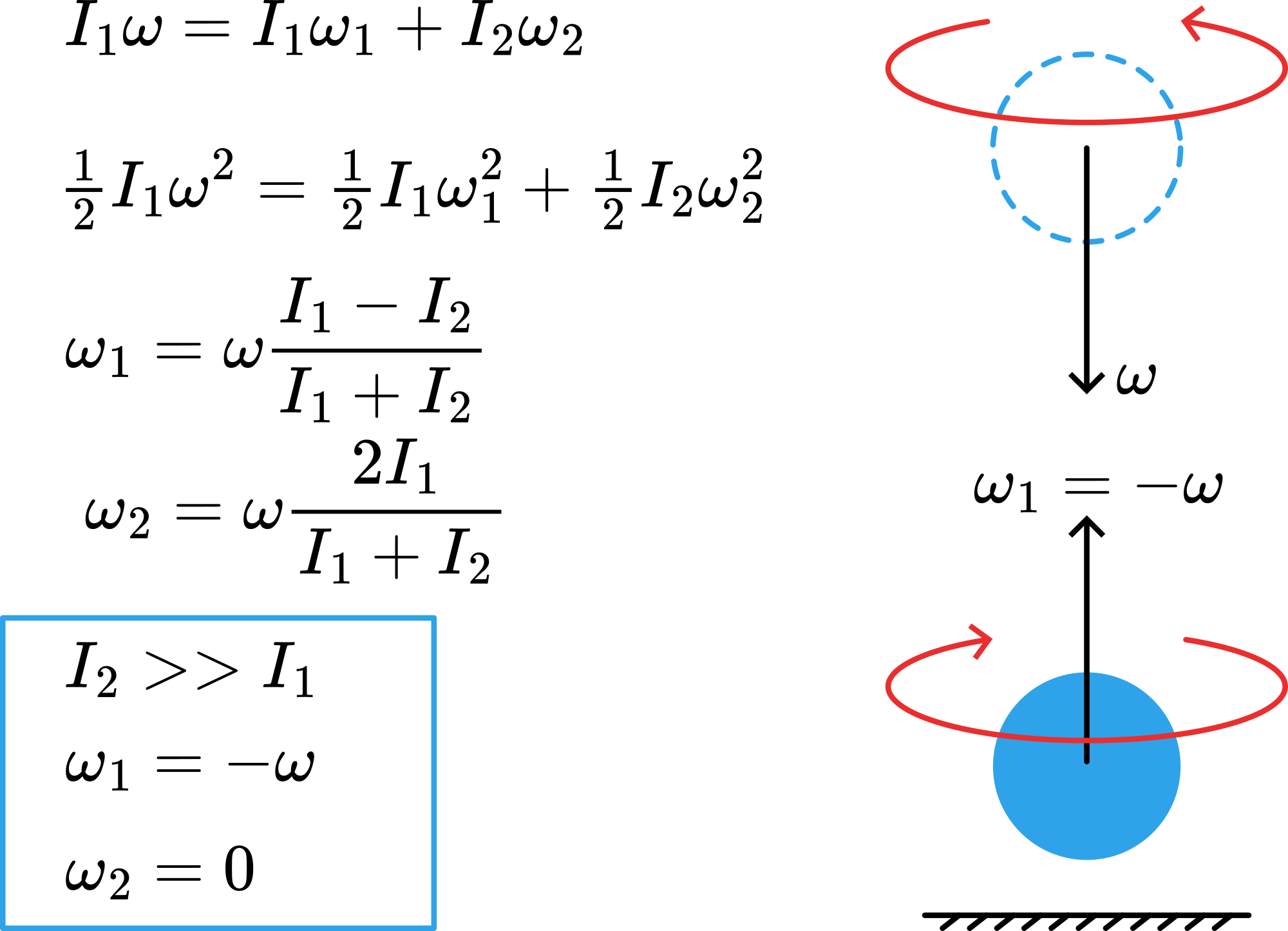

Figure 179 shows the explanation from a point of view of rotational dynamics. In order to perform this demonstration you really need a racquetball.

Fig. 179 .#

When, for instance, you use a superball, the ball continues to rotate in the same direction after bouncing. In order to get a reversal of the sense of rotation it is wise to study again the correspondence between translational and rotational laws:

In translational situations we get a reversal of velocity due to the elastic bounce on the floor; temporarily the kinetic energy is stored in potential energy of the materials (linear springs: \(U=1 / 2 k x^{2}\)). To get at bouncing such a situation for rotation we need to store the rotational energy by means of torsion ( \(U=1 / 2 c \theta^{2}\) ). When using a superball, this material is too massive, too stiff, in order to store the rotational energy in torsion. The ball slips over the floor and looses part of its rotational energy in that dynamic friction before it bounces up again. After a couple of bounces all rotation is lost. From a point of view of rotation, a bouncing superball bounces not elastically.

When trying a basketball we will see that it shows the predicted change of direction of rotation just a little (when the speed of rotation is not too high). The difference, when compared to the superball, is that a basketball is thin-walled, while the superball is massive. The thin walled basketball can make a little torsion at its bouncing contact while the superball cannot. This leads us finally to the racquetball that can make a relatively large torsion (in combination with a high coefficient of static friction with the floor). To show this torsion we have a racquetball with two straws stuck to it (see Diagram C). While the camera sees the two straws in line, one behind the other, you can show the possible torsion by forcing it that way by your hands.

Sources#

The Physics Teacher, pag. 550-551 (Vol.42), Vol. 42

Mansfield, M and O’Sullivan, C., Understanding physics, pag. 166